Les Contes de Poindi, Jean Mariotti, 1941

- New Caledonia, #1

- Paperback, $4.67 from Amazon

- Read July 2016

- Rating: 4/5

- Recommended for: wise children

OK. Let’s talk about New Caledonian crows. New Caledonian crows are the chimpanzees of the bird cognition field (not the guinea pigs, because guinea pigs are not that bright and you don’t really use them for complicated stuff; the guinea pigs of the bird cognition field are pigeons). That is to say, they’re smart and interesting and have complex behaviors and are thus used for lots of research that aims to explore questions such as “how the hell can birds learn to make and use tools when they don’t even have prefrontal cortices?” A New Caledonian crow named Betty “astonished the world by bending a straight piece of wire” to make a tool that she then used to retrieve a piece of food in 2002 (you might be overselling that one a bit there, Guardian–I’m sure animal cognition researchers were astonished but the proportion of the world population comprised of animal cognition scientists is probably not significant). Until the 1970s it was thought that only humans were capable of using tools, and then it gradually became apparent that lots of other animals do too; then it was thought that the difference between humans and animals lay in the ability to make tools, but that was also a wash because lots of animals make tools too. Then I think there was something about how only humans are able to knap flint, which seems like a really arbitrary standard on which to base your conclusions about animal cognition, and also apparently is not true anyway.

Now it turns out that other New Caledonian crows also spontaneously bend twigs into arcs, which some people argue makes Betty’s behavior less special for reasons I won’t go into here (but you can read this Science article, “Was Betty the crow a genius–or a robot?” if you’re interested) (lest you get your hopes up I should warn you that they don’t mean an actual robot; this title is what passes for clickbait in biology). This does not mean, however, that the various New Caledonian crow research labs that have sprouted up in the last two decades are going to close up shop.

All of this is to say: my only previous knowledge of New Caledonia was entirely comprised of a few facts about New Caledonian crows. And when I started reading New Caledonian literature I didn’t even make the connection, and I might never have if the crows hadn’t shown up in Les Contes de Poindi, with their smart and playful and troublemaking behavior so accurately depicted that I recognized them immediately.

This is one of the things I loved about the book. It’s a fable, sort of, and a children’s story, sort of, and full of talking birds with secret missions and eels with complex social hierarchies and magical fish that are actually dead heroes in disguise, and yet the behavior of these anthropomorphized animals is so lovingly and truthfully captured that even when I didn’t know the french name of the species, I could often recognize it by its actions alone.

There are two stories, one nested within the other. Poindi, a kanak warrior in the days before European contact, is out hunting during a time of scarcity with his son Aïni. Aïni accidentally scares a crow; the crow then calls all his friends and they hound the human hunters for miles, cawing and cackling and scaring away all the game. Tired and far from home, Poindi and Aïni stop for a rest. They catch an eel and while they are waiting for it to cook in their earth oven, they see a turtledove (tourterelle in french, but based on the description, most likely Mariotti was referring to a cloven-feathered dove) stealing a candlenut from the crows, who have been dropping the nuts onto hard stones to crack them. This inspires Poindi to tell Aïni the Story of the Dove and the Crow, which relates the quest of a heroic dove named Joli-Bec to call in a favor from the Queen of the Eels and save her people from starvation. Following the Queen’s enigmatic advice, Joli-Bec figures out how to trick the crows into smashing candlenuts so that she and her conspecifics can eat the meat.

When this story ends we find ourselves already midway through the next tale: the Story of the Eel and the Sunfish. The eel that Poindi and Aïni have caught turns out not to be an eel at all, but Tamata, a dead hero from the distant past who occasionally returns from the land of the dead (down at the bottom of the ocean behind a giant clam’s mouth) to check out what the living are up to. If he had been awake, the story tells us, Poindi would have recognized his human gaze and left him, but he was asleep and so Poindi doesn’t figure out that anything is up until they open up the oven and find the eel still completely raw. One of the eel’s fins lodges itself under the wing of a notou (goliath imperial pigeon) that Poindi has shot, and when Poindi returns to his village and presents his catch to the priests (so they can choose the best bird as a gift to the gods) they are horrified to see that half the bird is scaled and finned like a fish. In the face of this abomination, they tell Poindi that he must voyage to the ocean and catch a fish with human eyes to ask for further instructions; if he fails, he will be put to death to appease the gods. The rest of the story details Poindi’s and Aïni’s adventures as they struggle to complete this quest in the allotted time.

I got this book by accident. I ordered another work of Mariotti’s (Tout est peut-être inutile—“Everything may be useless”) and was sent this instead; it turns out they have the same ISBN. The company refunded my money and told me not to bother returning the book, so I got this beautiful illustrated volume for free. I’m so glad fate intervened in this way, because the other one was probably depressing and this book was engaging and enjoyable. I wanted to find out what happened next. Even though the happy conclusion seemed inevitable, the twists and turns the story took to get there were unpredictable. It’s not like anything I’ve read really, because it’s a fable, potentially childish, and yet told with a writerly and even masterly care and precision, neither the silliness of the just-so stories nor the dryness of anthropological retellings of myths. Oral stories often lose their appeal when written down, becoming wooden and overly simple. These stories were supposedly told to Mariotti, who was born in New Caledonia to European parents before emigrating to France as an adult, by his Kanak nurse when he was a child. He succeeds in preserving these stories, breathing life into them along with his own personal style, and passing them on in a mature and literary form.

Sounds like a serendipitous mistake! Your description of it as a fable that is not childish reminds me of Homeless Rats, the book I read for Libya. It features talking animals, but is not childish at all. I see that it’s already on your list, so that’s good!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, I found it interesting and difficult to characterize. I wanted to compare it to Kipling, but I haven’t read Kipling as an adult and remembering back I realize his books are…problematic, to say the least. I couldn’t really think of any other fable-type books that aren’t meant for children. I look forward to reading Homeless Rats! I wonder when I’ll get to Libya. Probably about 2040 at the rate I’m going.

LikeLike

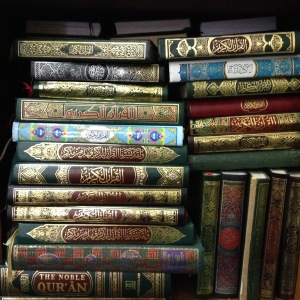

Book sounds intriguing. I’ll bet Wyatt would enjoy it. Gorgeous photos.

LikeLike